Sylvia

a book - a painting - a friend

I. Sylvia (1993), Leonard Michaels.

I am an impulsive book buyer. I have tried to stop myself from buying books, considering the fact that I still have piles and piles of unread gems at home (in Marseille, in Amsterdam). The no-buy policy never lasts. Last week I bought Zelda Fitzgerald’s Save me the waltz, a book overflowing with long complex sentences, beautiful descriptions that make you dizzy. You can’t really rush through it, but sometimes you have to, in order not to get drunk on phrases like these:

“Some day she will awake to observe the plants of Alpine gardens to be largely fungus things, needing little sustenance, and the white discs that perfume midnight hardly flowers at all but embryonic growths; and, older, walk in bitterness the geometrical paths of of philosophical Le Nôtres rather than those nebulous byways of the pears and marigolds of her childhood”

I abandoned the book yesterday for an antidotal shot of clean sentences: re-reading Leonard Michael’s Sylvia.

I bought this book because it was recommended by Molly Young, literary critic and writer whose taste I trust one hundred percent. I think it was recommended in an Instagram story as a tragic romance and I bought it immediately, online, used.

Second hand buying often brings the limitation of not being able to choose the exact cover you want, so instead of the nice painting, I got the black and white photo of a woman laughing in a white lace brassiere.

I brought it with me to Morocco, and felt awkward reading a book by myself outside with a topless woman on the cover, so I folded the cover backwards and put some tape on there. I had to untape it today because the french waiter asked me to show him what I was reading.

Sylvia is written by Leonard Michaels, a jewish American author who got appropriate appreciation for his work only after his death. He published mostly collections of short stories. This novel originated as a short story based on a real life relationship he had in the early 1960’s in New York. He extended the story and republished it in 1993.

The story is written from Leonard’s point of view1 and tells us about the relationship between him and 19 year old orphan Silvia, which is, euphemistically speaking, toxic. The narrative makes it seem that this is mostly due to Silvia’s mental issues, incoherent behavior and rage. She is drop dead gorgeous, but always complains about her looks. She Leonard’s way of describing their time together is honest, plain, without too many adjectives. It’s stripped down, as they say. It is effective. Their first encounter takes place in Sylvia’s house in New York, Leonard visiting her roommate who is a friend of his. She has just stepped out of the shower, which is located in their open kitchen, and is brushing her hair:

“A plastic curtain kept water from splashing onto the kitchen floor. She said hello but didn’t look at me. Too much engaged, tipping her head right and left, tossing the heavy black weight of hair like a shining sash. The brush swept down and ripped free until, abruptly, she quit brushing, stepped into the living room, dropped onto the couch, leaned back against the brick wall, and went totally limp. Then, from behind long black bangs, her eyes moved, looked at me. The question of what to do with my life was resolved for the next four years.”

We don’t dwell in the narrators head too much, besides in the short journal entries included. Instead, the book puts a lot of weight on the physical context of the characters. We are often reminded of their surroundings of their claustrophobic New York apartments, invested by roaches, fleas, even rats. They live in a mess, but don’t seem to care enough to change it:

“There was no desk in the apartment, but Sylvia didn’t need such conveniences, didn’t even seem to notice their absence. I don’t think she ever complained about anything in the miserable apartment, not even about the roaches, only about me. She studied sitting on the edge of the bed in a mess of papers.”

They fight every day, for reasons no so much unknown, as incomprehensible to Leonard. Sylvia is heavily attached to him, but does nothing but push him away with screaming rage. He stays. His life becomes smaller and smaller, as she won’t allow him to leave the house so much, does not allow him to leave the bed to write his stories, and sleeps with all of their mutual friends.

As Sarah Manguso writes in her blurb on the back of the book: “the ending is as shocking as that of any thriller”. Qualifying the book as a thriller goes against my romantic heart, but being in love with a sick, manipulative person can drive one to very scary places. And even though Sylvia is very smart (she passed her classic studies, which she does not care about and studies for between midnight and 5 am, from their bed, with excellent grades) she is very sick indeed.

“In the throes of her hysteria, her voice might suddenly become cool and elegant, and she’d make a witty remark, as if she were detached from herself and every quality of the moment was clear to her - the hatefulness of her display as well as my startled appreciation of her wit. I took this as a good sign, thinking it meant she wasn’t really nuts. She felt the same way about it.”

This is maybe why she does not seek help. Deep down carrying this fake believe that since she is (sometimes) aware of her behavior, equalling that she is actually in control of it too. Leonard makes appointments for her with psychiatrists, which she refuses to attend, only for him to go in her place and rant for an hour and a half about their relationship. When he leaves, the doctor calls after him: “This is very serious”.

It ends seriously.

II.

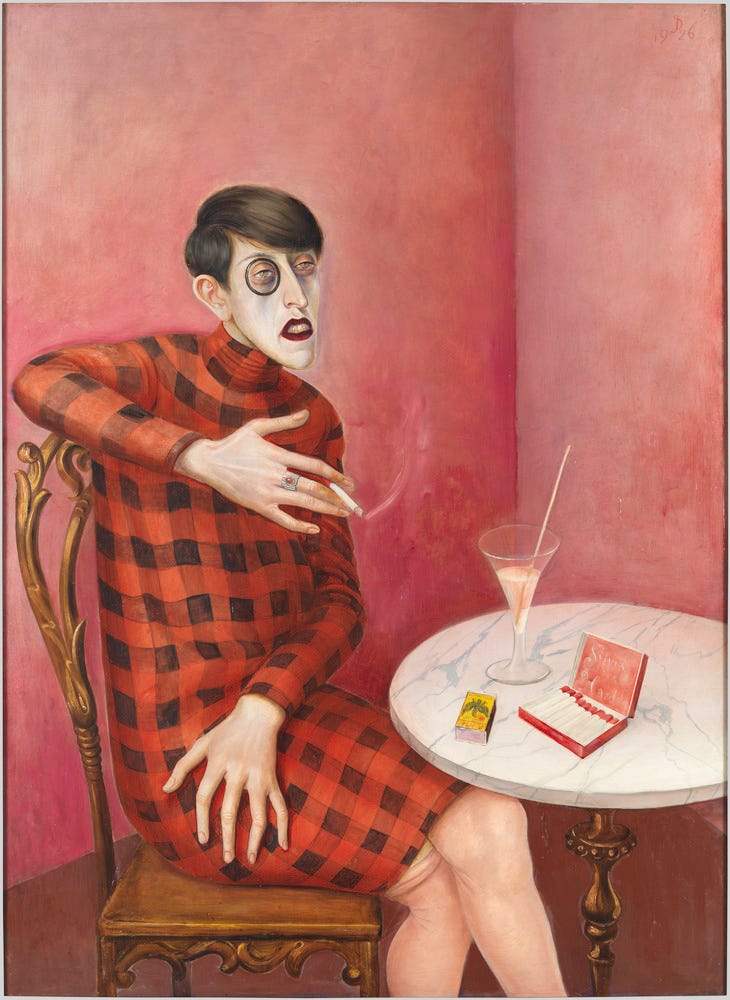

Portrait of Sylvia von Harden (1926) by Otto Dix.

Sylvia von Harden was a journalist, literary editor and poet living in Dresden. She grew up in a posh environment (father was a banker) but luckily she had an eccentric lesbian aunt that turned her into, here we go, a feminist. Otto Dix was a german painter who formed part of the Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity) in Germany. In Von Harden’s words, they met on the street and he asked (begged) her to sit for him:

“I must paint you! I simply must! … You are representative of an entire epoch!”

“So, you want to paint my lacklustre eyes, my ornate ears, my long nose, my thin lips; you want to paint my long hands, my short legs, my big feet — things which can only scare people off and delight no-one?”

“You have brilliantly characterized yourself, and all that will lead to a portrait representative of an epoch concerned not with the outward beauty of a woman but rather with her psychological condition.”

Another Sylvia, not so impressed by her own physique. She, however, finds her worth in other areas. She is what the interwar germans call: die Neue Frau. Charismatic, opinionated, intellectual, emancipated. The portrait is supposed to represent a woman not for her beauty, but for her character, something rather uncommon in that epoch. Postwar german artists were traumatized, and no longer interested in poetic lovely expressionist paintings. They did not want to paint dreamy landscapes populated by their bourgeois clients, wearing big skirts, carrying umbrellas. They valued philosophers and writers, and, slowly, realized that these intellectuals could also be women.

I saw this picture for the first time in an art history class in university, and I don’t think it ever left my mind. Clearly, I have internalized this woman as the ideal to strive for, with her cigarettes, her martini, her marble table, her pink and red, and her look of “whether you like it or not, young man, I am going to be right”.

III.

In high school the first friend I made was called Joelle and her second name was Sylvia. She hated it, we were never allowed to call her that. When after a few days of school, my class was the first to embark on our ‘bonding camp’, I was so eager to sit next to her on the bus, and so scared I would arrive late and somebody else would have already taken that seat next to her, that I cried on the back of my mom’s bike, who was dropping me off, afraid that she was going to slow.

It was a crazy bike drive, I remember my sister came along as well (I am tempted to she came just to wave me off, but I bet there was a more logical reason for it, like that they were seeing the dentist after). My mom carried me on the back and my week-bag on the front of her bike. We arrived at the ferry and it was full, but I INSISTED we take it, to arrive sooner. We squeezed on. It was maybe the fullest ferry I have ever taken. There were bikes on the ramp that were lifted up diagonally when it closed, back wheels in the air. Ingrained in my memory is the vision of my sister squashed between her bikes steering wheel, and another bike’s steering wheel pushing her in the back, this one being diagonal, all the weight of it pushing down on my 10 year old Lotta.

My mom remembers too.

I sat next to Joëlle, Sylvia, on the bus. She was my first friend in high school, and we were in the same class for all six years we spent there. We called her Jo. My father still calls her Jojo.

We also called her Panter Poesie because she loved leopard print. She loved it so much that her room made you dizzy. She wanted four children, the first at 24. She was the one who didn’t do babysitting, like most of us, but had actual weekly shifts in a lunchroom, and later at Domino’s pizza. She saved all of her money and moved out of her parents house later than we did, as not to pay absurd Amsterdam rent.

She lived in the South-West of the city. I slept over at her place often, especially the first years. We made stop motion videos of webcam photo shoots in our pyjama’s, Miley Cyrus playing in the background. Years later we would scream in horror at the pictures of our faces, still children, with braces, and all videos were deleted off of Youtube.

At her house I was drunk for the first time. The boy who was to be my first boyfriend was too, there is a flash picture of us embracing, taking with a BlackBerry I assume. We did not have our first kiss that night. Joëlle’s parents were present during the party, hidden somewhere in a different part of the house. Later, her father made my then boyfriend feel better saying the reason he threw up in the toilet that night must have been due to the warm beer he was drinking, not his (and all of our) total inexperience with but immense thirst for alcohol.

I spoke about her just yesterday, when L. mentioned Goodfellas and I know that for the longest time that was her favorite movie. I explained Jo and I both loved cinema, but our tastes were different. She liked Mad Max, I liked Moonrise Kingdom. We both liked Gossip Girl, and honoring my obsession with Blair Waldorf, who loves Holly Golightly, one day she gave me the DVD of Breakfast at Tiffany’s.

I think about Joëlle, Sylvia, often. She had her baby at 26. She is a home owner. Unlike so many of us, she knew what she wanted. And then she got it.

I choose to refer to him by his first name, for that is also how he and I will refer to Sylvia. It feels weird to address them with different levels of supposed respect.

I love this piece and how you decided to structure it. We also share a love for the name Sylvia (love the book, didn't know about the painting). It's nice to feel accidentally connected to a stranger.